Buyer Beware – Investing in China

If you sell every person in China a Coke, you’ll be a billionaire many times over.

Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba Group, put that expression into action. His sights were set much further than one Coke: he wanted to sell everything to the people of China.

After graduating from university in 1988, Ma applied for nearly 30 different jobs. In his autobiography, Alibaba – The House That Jack Ma Built, he retells that period of his life.

“I went for a job with the police; they said, ‘you’re no good.’ I even went to KFC when it came to my city. Twenty-four people went for the job. Twenty-three were accepted. I was the only guy rejected.”

By 1995, Ma registered the domain chinapages.com, building it into Alibaba Group, the largest company in China over the next 20 years. Alibaba went public in the U.S. in 2014, raising $25 billion and becoming the largest IPO in U.S. financial history, a record that still stands today.

Ma wrote his own Hollywood script – from fast-food rejection to the richest man in China inside of 25 years.

The sequel hasn’t been nearly as good.

Last October, Ma crossed the Communist Party, of which he is a member, in a globally televised speech accusing the Chinese government of stifling innovation. Ma directly contradicted the rule of law in China that big business should never become the master of the state. It was a bold and perhaps foolish decision.

For that, he got his wings clipped.

By December, major media organizations began reporting Jack Ma had disappeared. This coincided with a regulatory crackdown on Alibaba from the Chinese government.

The pending IPO of Ant Group – an online finance company spun out of Alibaba – was canceled. Authorities in Beijing ordered an investigation into monopolistic practices at Alibaba resulting in major fines. Ant Group was then ordered to divest some of its operations.

In a span of months, the Chinese government showed it could exert more control over Alibaba than the founder of the company.

Nearly three months after Ma’s disappearance, he resurfaced in a short video that many observers compared to a hostage video.

The message was clear: In China, when big business pushes back against the government, the government is going to win.

The investment case for China is widely known. It can be watered down to strong long-term fundamentals, economic expansion, and rising consumer wealth.

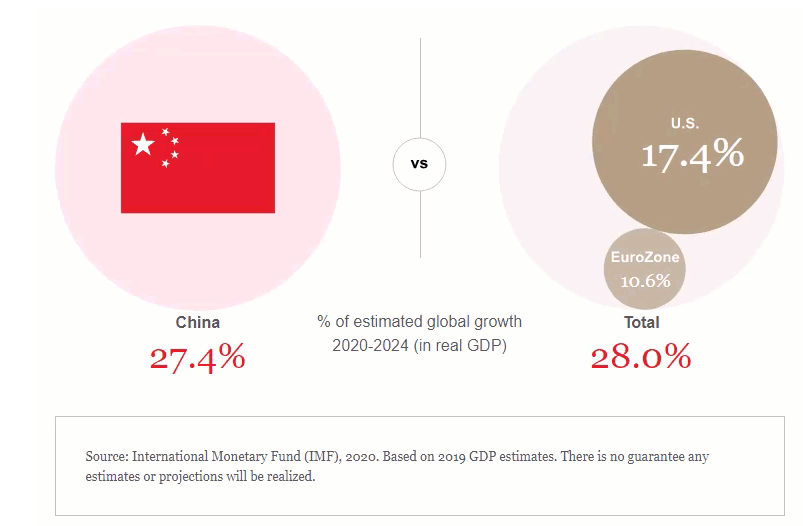

Per Matthews Asia, an investment manager focused on emerging markets, China may contribute roughly the same percentage of global GDP growth as the U.S. and EuroZone combined in the five-year period through 2024.

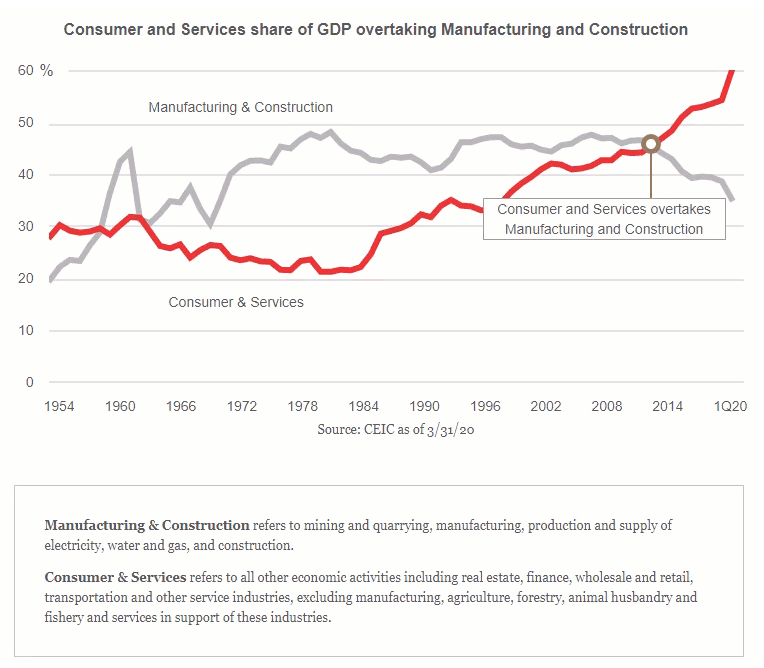

The Chinese economy has been moving away from capital-intensive businesses and growing through asset-light businesses enabled by technology. Many people like to compare China’s economy today to what the U.S. economy was 25 years ago.

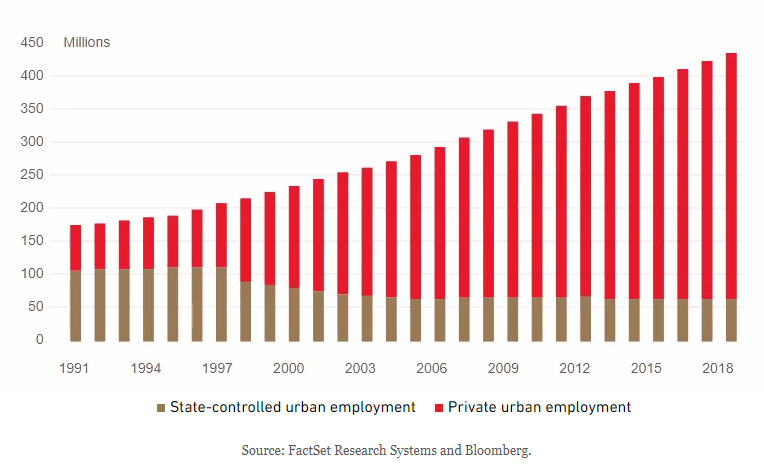

This has allowed China to rebalance itself towards the private sector, reducing the need for the state to create job opportunities.

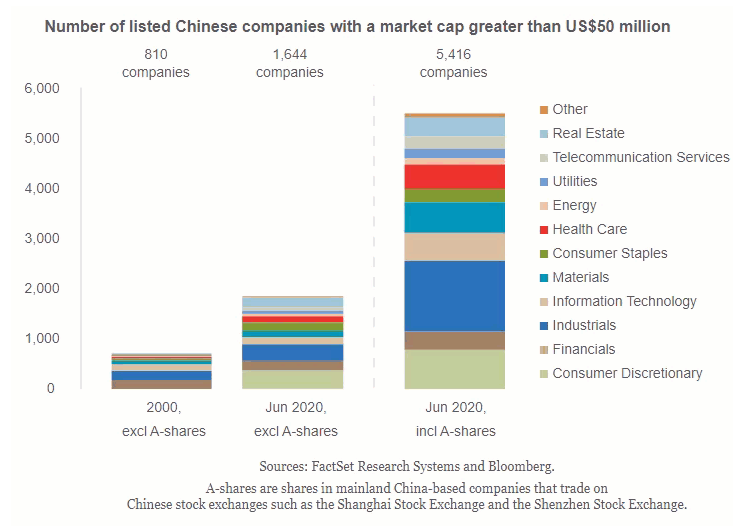

China now has more than 5,000 public companies with a market cap greater than $50 million, up from fewer than 1,000 companies in 2000. The liquidity, depth, and breadth of China’s public companies make its capital markets one of the strongest in the world, likely the second strongest behind the U.S.

Technological innovation, continued growth in entrepreneurship, and the rising wealth that follows will likely make China an attractive place to invest for the next few decades, if not longer.

From 10,000 feet, China is an attractive place to invest. Under the hood, it’s not as pretty.

Alibaba is the biggest and most high-profile Chinese company, but there have been other odd situations involving Chinese companies listed on U.S. exchanges in recent months and years.

- Last week, Didi Technologies, the “Uber of China,” went public with a market cap of nearly $80 billion. Less than a week later, Chinese authorities announced they were potentially suspending the company from a Chinese app store. The stock has fallen 25% since the IPO.

- In January, the New York Stock Exchange delisted three Chinese telecom companies – China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom – after they were accused by the U.S. government of sharing user data with Chinese government officials.

- In early 2020, Luckin Coffee, the “Starbucks of China,” was accused of fabricating hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. The company had a market cap of $13 billion before falling 95% and being delisted from U.S. exchanges.

This list highlights only a few extreme examples but will likely grow over time.

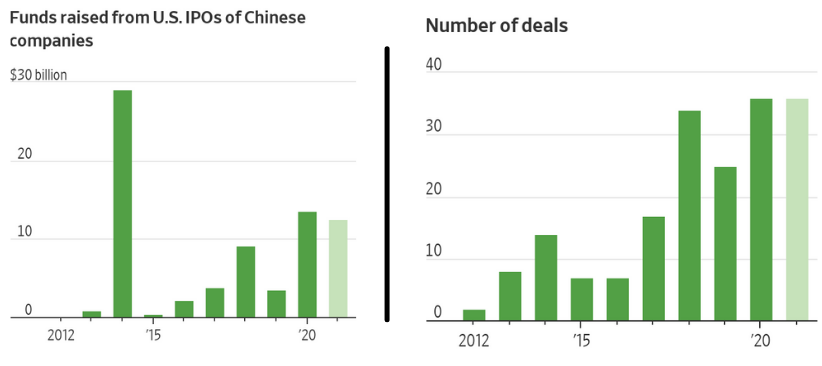

In 2021 alone, 36 Chinese companies raised a total of nearly $13 billion in U.S. IPOs, roughly the same amount as all of 2020, according to Dealogic.

Didi’s $4.4 billion IPO last week was the biggest by a Chinese company since Alibaba’s.

Source: Dealogic via Wall Street Journal, data for the year through July 5, 2021.

China is the world’s second largest economy but remains an emerging market and, with that distinction, carries more risk than established, open markets like the U.S or Europe.

Money will always flow toward opportunity and there will be more Jack Mas in China’s future. A steadily growing economy, the introduction of new technology, and a billion consumers will likely ensure it.

For this reason, investing in China should remain desirable despite cases of fraud and rigid government control. Most index ETFs that invest in emerging markets hold a large allocation to China, roughly 30-40 percent, giving investors broad, diversified exposure.

But if you’re buying individual Chinese companies, buyer beware.

This is intended for informational purposes only and should not be construed as personalized investment advice. Please consult your investment professional regarding your unique situation.