“Social Distance” Yourself from Panic by Following the Lessons of Past Bear Markets

On top of health concerns, many people are worried about their financial wellbeing. This is the time to lean on your trusted financial professionals to provide clarity on your specific circumstances and to put today’s coronavirus crisis in perspective relative to previous health or financial driven crises we have endured.

These are no doubt very uncertain times for the health of our loved ones and that of the rest of the world with the rapid outbreak and spread of COVID-19 (coronavirus). On top of health concerns, many people are worried about their financial wellbeing. This is the time to lean on your trusted financial professionals to provide clarity on your specific circumstances and to put today’s coronavirus crisis in perspective relative to previous health or financial driven crises we have endured.

The stock market recently entered a bear market (decline of 20% or more) – the fastest one on record happening in just 19 days (S&P 500 Index). The next fastest one was 36 days in 1896. Many investors wonder if there is something they should do. Should they try to time the market by cashing out now and waiting for things to improve? Savant clients know that our answer has always been a consistent and confident “No!” Feelings or predictions about market returns are definitely not good reasons to change your investment strategy. However, we thought it would be interesting to take a look at previous bear markets to evaluate the risks of attempting to time the market’s recovery.

Historical Bear Market Data Can Be Helpful

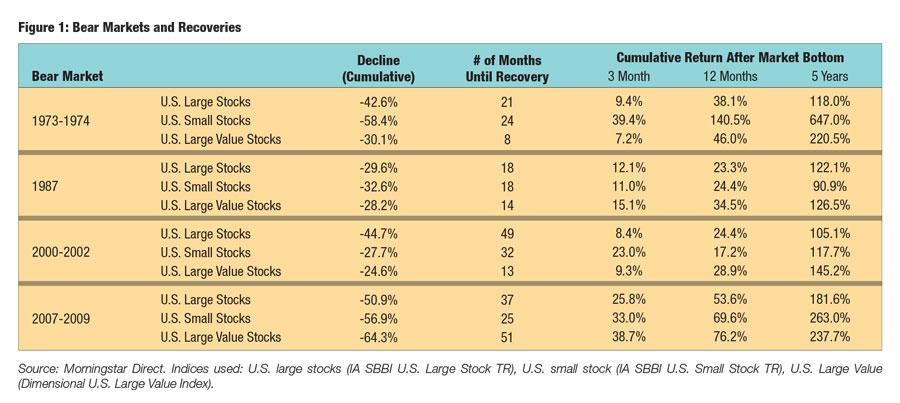

Figure 1 shows the results of past bear markets and recoveries for the various U.S. stock segments. It shows the total decline experienced during the bear market and the returns that investors experienced during the subsequent recovery. For example, from 1973-1974, U.S. large cap stocks declined a staggering 42.6%. Within just three months from hitting the bottom though, investors had experienced a 9.4% gain. After 12 months, stocks rose 38.1%, and investors had recovered a significant portion of their losses. An investor that held on for the next five years would have experienced an impressive 118.0% cumulative gain. The results are similar for other bear markets in 1987, 2000-2002, and 2007-2009. In each case, it shows that once the market reaches its bottom, the recovery can be extremely fast and very intense. An investor who missed even a few months of a recovery could have significantly affected their long-term returns.

The same holds true for U.S. small and U.S. large value stocks, other market segments that investors have exposure to in Savant portfolios. Even when the initial decline was sometimes harsher, the recovery was often faster and more intense than that of U.S. large cap stocks. Interestingly, the 2000-2002 bear market that was driven mostly by large technology stocks was not quite as bad for small stocks. However, small stocks still went along with the overall market recovery and rose 117.7% over the next five years. Furthermore, U.S. large value stocks had the quickest and strongest recovery after that bear market. The figures show the difficulties of market timing. Not only is it difficult to predict the exact bottom of a bear market, but it is also very costly to miss even a small portion of the market’s recovery.

Putting Recessions in Perspective

While extreme market volatility is startling, it comes from the belief that the coronavirus will have a negative impact of trillions of dollars on the economy and that a global recession is more likely. First quarter 2020 corporate earnings may not reflect the impact we are likely to see in the second quarter and the rest of 2020. Furthermore, the shape of this future recovery is unknown. There is hope for a rapid recovery to follow on the heals of the bear market plunge we just experienced, but it is too early to gauge.

Research by three respected financial institutions addresses the recession issue from a historical perspective. The first study by The Vanguard Group found that recessions are very unpredictable. Economists need to look at past data before they can officially mark the start of a recession. For example, the recession of 2001 ended in November; that same month, the National Bureau of Economic Research announced that a recession had officially begun in March. Therefore, even if a recession did start recently, it might not be officially declared until September. Furthermore, the Vanguard study found that there is not a predictable relationship between economic growth and the timing of stock market returns. Of course, an expanding overall economy is good for stocks, but stock prices can drop even if the economy is growing. Similarly, if the economy officially enters a recession, it does not necessarily mean that the stock market will decline further.

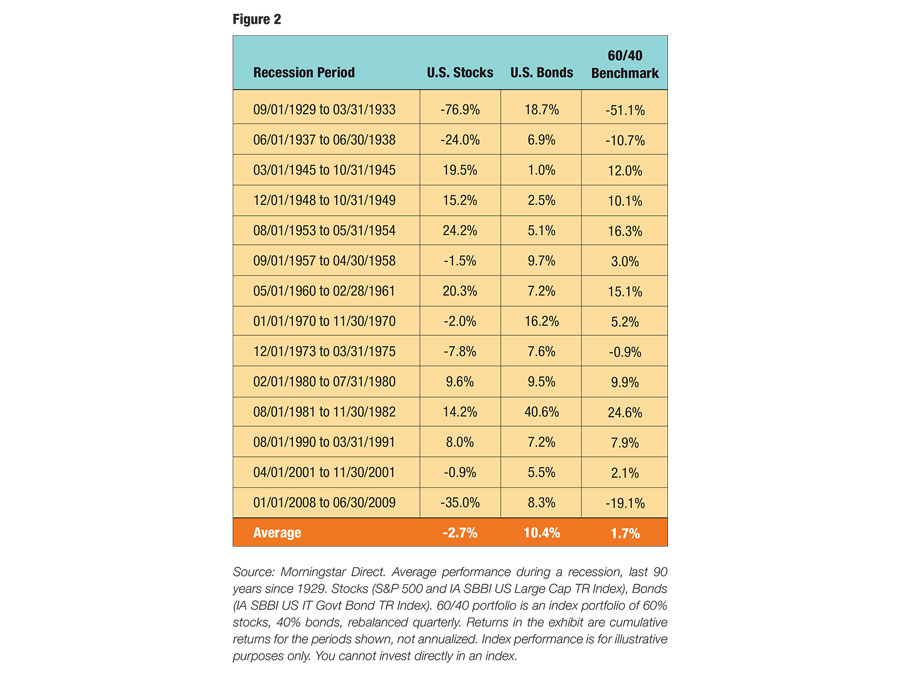

In fact, Figure 2 shows U.S. stocks actually posted positive returns during seven of the last 14 recessions dating back to 1929. While the returns of stocks were mixed, bonds generated positive returns in all recessions. This is the time when bonds shine and temper stock market volatility. As a result, a blended 60/40 index portfolio as illustrated had an average return of 1.7% during past recessions, with only four posting negative returns. If we leave out the very early Great Depression, the average return is 5.8% for the blended 60/40 index portfolio.

Historically, stock prices decline in the early stages of a recession and recover significantly toward the end. This is why the stock market is often considered a leading indicator of recessions. Once a recession has been officially determined, the stock market has typically already begun its recovery.

Stocks Will Resume Their Upward Climb

It might be hard to believe right now, but over the very long term, the stock market is fairly steady. The average annual return from investing in the S&P 500 Index from 1926-2019 was 10.2%. Over that timeframe, stocks earned positive returns in 69 out of 94 calendar years or 73% of the time. The average return during these good years was an amazing 21.3%. Of course, in order to capture these positive returns, investors must bear the risk of negative returns and bear markets. For the 25 negative years in the past 94 years, stocks lost an average of 13.2%. History shows that even after terrible years, the market has always recovered, resuming its upward climb over the long term.

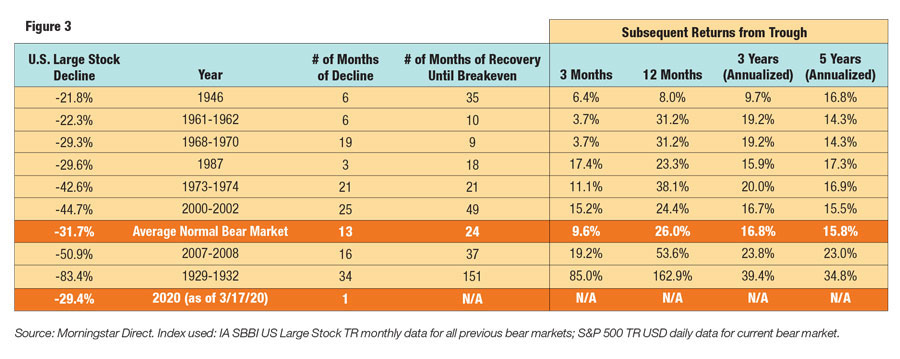

Figure 3 puts the current market decline in perspective. It shows the history of major bear markets since the Great Depression sorted by the total percent decline of the S&P 500 Index. For example, in 1946 investors lost a total of 21.8%, while the bear market of 2007 was much more severe (stocks lost 50.9%). These previous bear markets show that investors lost 31.7% in an average bear period that lasted 13 months. Notice that after every bear market, stocks recovered and experienced above-average returns. After the market reached its bottom, the average recovery returned 15.8% per year for the next five years. The Great Depression was an extreme period. Stocks lost an astonishing 83.4% over the course of almost three years. The recovery was equally remarkable as stocks jumped 162.9% in the first year after the market bottom and averaged 34.8% per year for five years.

This bear market was sparked by a health crisis and exacerbated by an oil price war, so we do not believe this is similar to the 2008 financial crisis which stemmed from financial excess in the mortgage market and other imbalances. Strict social distancing coupled with coordinated monetary and fiscal stimulus packages to help cushion income disruption for households and small businesses will go a long way to get us through this. While the start of the global response seemed slow, there has been a significant effort to put disease response measures into action.

Since recessions and market declines are so hard to predict, and the cost of missing part of the unpredictable recovery is so high, patience is clearly an investor’s best strategy. While stocks could stay lower for longer, we are confident that a recovery will occur. Time and again history shows that patient investors, who remained invested in diversified equity portfolios, were rewarded.