The Debt Ceiling (Again): What’s Next?

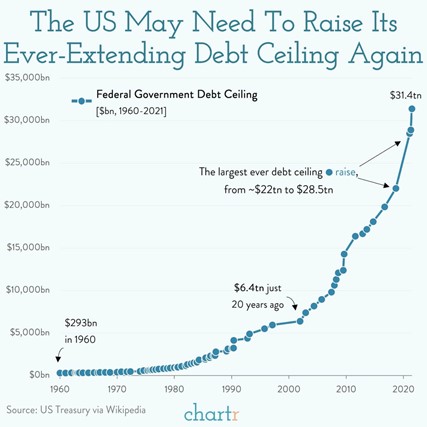

On January 19th, the U.S. hit its debt ceiling at a staggering $31.4 trillion. Raising the debt ceiling, which has been done 78 times since 1960, requires Congress to set a new limit. We never heard much about the process for many of these raises; however, in more recent history during 2011 and 2021, it became a political debate. Furthermore, it appears we may be on track for heated discussions surrounding the debt ceiling this year.

Let’s first take a step back to explain what the debate is about. The debt ceiling is the highest amount of money the U.S. government is allowed to borrow to pay its bills. Once the debt ceiling has been reached, the U.S. Treasury can no longer borrow money – meaning it will have difficulty meeting payroll obligations, paying for government purchases, and borrowing money for future debt obligations. In interim periods like the one we’re in currently, the government typically implements “extraordinary measures” to prevent a default on paying its obligations. This may include suspending new investments into retirement plans for government employees until the debt ceiling is raised.

While we are still a few months from it potentially becoming a crisis (estimated to be sometime between June and October depending upon activity such as incoming tax receipts, interest rates, and other factors), markets are already pricing in the probabilities of potential outcomes given our deeply divided Congress.

If the debt ceiling is raised, does that mean more government spending? No. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen noted in 2021 that “increasing or suspending the debt limit does not authorize new spending commitments or cost taxpayers money. It simply allows the government to finance existing legal obligations that Congresses and Presidents of both parties have made in the past.”

Many are comparing today’s circumstances to those in the summer of 2011 when the U.S. came close to defaulting on its debt because of the impasse in Congress, as we have similar incumbent political positioning in place today. In 2011, the debt ceiling was raised at the eleventh hour and only after a major credit rating agency downgraded U.S. Treasury securities below the highest AAA credit rating. This caused considerable stock market volatility as well as elevated yields for Treasuries as the risk of default rose.

While there are still several months until the extraordinary measures run out in 2023, investors are already anticipating dramatic debates over the government budget and debt ceiling. As has been the case historically, we expect lawmakers to hash out the details, as it is in no one’s best interest for the U.S. to default on its debt obligations. Failing to agree on a new debt ceiling could have the negative effect of investors losing confidence in the U.S. throughout the global financial system. As investors, we should continue focusing on what we can control, including properly positioned portfolios to help support our unique circumstances.

Source: Chartr